Blog

Young and Adrift: Measuring Youth Disconnection in America Today

This blog post originally appeared in the Huffington Post on September 26, 2016. You can access the original article here.

Co-authored with Alex Powers, Program Associate at Measure of America and Marina Recio, Program Assistant at Measure of America

In July of last year, a group of over a dozen high-profile companies, including Starbucks, Microsoft, and Walgreens, formed the 100,000 Opportunities Initiative and pledged to hire 100,000 young people not in school or working over the next three years. Last month, the Initiative, which has grown to about fifty leading U.S companies, announced that it had met its hiring goal two years before the deadline.

The quick growth of the Opportunities Initiative reflects a rising concern in America about access to opportunity for young people—or rather, the lack thereof. A wide range of recent initiatives seeks to reconnect teenagers and young adults who find themselves detached from school and work, a group referred to as “disconnected youth” or “opportunity youth.” Far too many young people find themselves adrift, detached from the core institutions that give meaning to our lives and structure to our days. Roughly 5.5 million youth between the ages of 16 and 24 are neither working nor in school, about as many people as live in Minnesota or Maryland. Often these young people carry their scars of disconnection into adulthood, where they take the form of lower wages and marriage rates, worse health, less job satisfaction, and even less happiness.

Across-the-aisle consensus now holds that the social and economic costs of youth disconnection are far too high, for both young people personally affected and for society at large. The first step for action is identifying which young people are disconnected, where they live, and which socioeconomic characteristics and barriers to connection they share. Despite what some may think, disconnected youth are not a monolithic group, and all young people do not face the same risks of becoming disconnected.

While youth disconnection has been measured and analyzed for decades by governments in Europe, where these young people are called “NEETS,” (Not in Education, Employment or Training), the focus in the United States is more recent, and different methods for calculating youth disconnection can sometimes result in seemingly contradicting figures. Ultimately, better measurement means a better chance of success at preventing youth disconnection in the first place and reconnecting those who have fallen out of the mainstream.

Measure of America of the Social Science Research Council has taken a closer look at existing approaches as a first step in this direction. What follows is a guide to the differences and relative strengths of existing data on youth disconnection.

Defining Youth Disconnection

Taking the lead from years of work in Europe, a good basic definition of disconnected youth is this: teens and young adults ages 16 to 24 who are neither in school nor working. This is the definition that Measure of America has used in its data calculations and analysis on youth disconnection since its first report on the topic, One in Seven, published in 2012. It’s also the foundation for most other youth disconnection estimates.

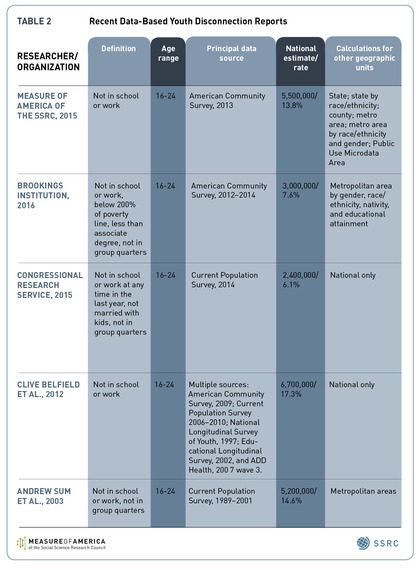

Some researchers have added additional qualifications to this core definition. The Congressional Research Service, for example, in their 2015 report, counted out-of-school-and-work young people who were both married to a connected spouse and parenting a child as connected, given that they engaged in caring labor in the home and were supported by the earnings of a spouse. In addition, they only counted those who were out of work for at least a year as disconnected. The Brookings Institution uses the core definition, but narrows it further to those below 200 percent of the federal poverty line and with less than an associates degree. These qualifications result in significantly smaller estimations of youth disconnection. See Table 2 below for the total U.S. estimate for each of these definitions.

Who Is Considered a “Youth”?

The age range most researchers have used since the 1990s for studying disconnection has been 16 to 24 years of age. Measure of America, Congress, the Congressional Research Service, the Brookings Institution, the Center for Law and Social Policy, and Belfield et al. have used this age range. Other organizations have used a 14 to 24 age range, including a 2008 Government Accountability Office report. The European Union’s standardized definition of their “NEETs” uses the age range 15-24, in large part due to the way their data are collected.

Data Sources

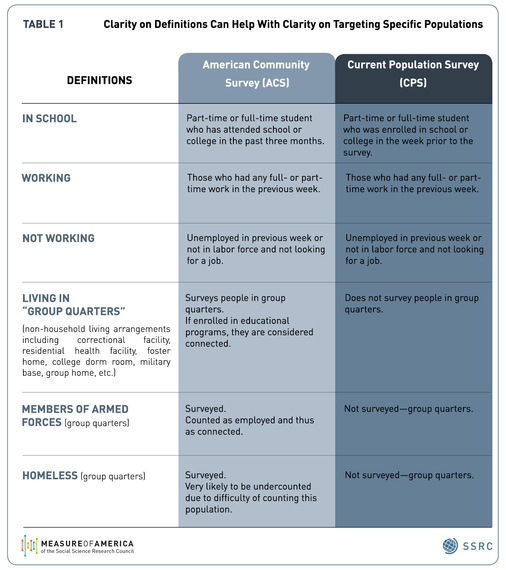

The two main government surveys available for calculating youth disconnection are the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual American Community Survey (ACS) and the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Using the ACS, Measure of America calculates that there are about 5.5 million youth in the 16 to 24 age range who are neither in school nor working, or one in seven young Americans. Each survey has advantages for understanding the challenges of this population.

The American Community Survey’s main advantage over the Current Population Survey is that the ACS includes a much larger sample size, making it possible to calculate youth disconnection rates in for counties, metro areas, and even smaller geographic areas as well as nationally and by state. It also allows for disaggregation by race and ethnicity and by gender. The ability to disaggregate data can reveal interesting and sometimes surprising insights lurking below national, state or even city-level data—like the impacts of racial segregation on white and black disconnection rates, or the stark inequality in disconnection rates by neighborhoods within large cities like New York.

Another advantage of the ACS is that it surveys young people in “group quarters,”—college dorms, jails and prisons, foster homes, and military facilities; the CPS does not survey those living in these residential facilities. A plus of the CPS is that it is an older survey, with data stretching back to 1940; this makes it possible to look at historical trends. See Table 1 below for further detail.

Conclusion

Lest this roundup leave the impression this is a complex, difficult-to-measure issue, this is not the case. The simple, basic definition and measurement are already a tremendous advance towards making visible a population that has for too long been living in the shadows. The efforts to further striate this population for various subgroups, whether for racial and ethnic groups, teenage boys vs. girls, particular neighborhoods or unmarried young adults, only serves to strengthen our ability to tailor policies and programs to address each group’s particular challenges and needs.